Guillain Barre Syndrome: A Case

Mar 27, 2024CASE

A 36 yo woman presented to the emergency department complaining of numb feet. “I can’t feel the pedals in the car when I’m driving…….. It started 2 days ago and seems to be increasing…. I mean, going up my legs”

There are no other symptoms and the patient is well otherwise. The only other history of relevance is that she had a recent chest infection. Relevant negatives is the history include no diabetes and no risk factors for stroke.

Examination reveals dual heart sounds and bilateral, equal air entry. There is symmetrical sensory loss of the feet and the distal lower limbs, with no other neurology.

Your immediate suspicion with this patient is that this is Guillain Barre Syndrome (GBS). The classic presentation is ascending flaccid paralysis, that is accompanied or preceded by paraesthesia. This is a classic presentation in a patient who has presented early in the course of the disease. However not all cases of this disease present in the classic fashion. It has varied presentations depending on the pathophysiology.

It’s low prevalence (100,000 annual cases worldwide), high morbidity (20% cannot walk unaided after one year) and mortality (5%), make it an important diagnosis, to not miss. However this low prevalence and its varied presentations, can make it a diagnostic challenge. The best way to make the diagnosis is to consider the diagnosis in patients presenting with neurological complaints. This review is based on a recent article in Am J Emerg Medicine(1)

What is the Cause and How does it present?

GBS is an immune mediated peripheral nerve disease. It is most likely caused by an infection resulting in antigens being created that resemble host cells/proteins. The body’s immune system then generates antibodies to fight these.

The various GBS clinical presentations depend on the targets of these antibodies:

- Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (AIDP)

- Antibodies are directed towards Schwann cells

- It is the most common form of GBS

- Classic findings are ascending weakness and decreased reflexes.

- Acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN)

- Antibodies directed towards the axolemma and nodes of Ranvier.

- Associated with greater extremity weakness

- Miller Fisher Syndrome

- Ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and areflexia, without weakness

- Cervico-Brachial-Pharyngeal Variant

- Ptosis, difficulty swallowing and upper extremity weakness, with preservation of sensation and power in the lower extremities.

- Sensory Ataxia Variant

- Sensory loss with no weakness

- Pandysautonomic Variant

- Orthostatic hypotension, ileus, urinary retention, areflexia and ataxia without motor weakness.

Phases of GBS

- Acute Phase ( 0-2 weeks of symptom onset)

- Progressive Phase (2-4 weeks after onset)

- Plateau Phase(>4 weeks after onset) which may last for months

Clinical Presentation

The most common presentation is:

- Symmetric ascending flaccid paralysis

- This is preceded or accompanied by bilateral sensory changes such as paraesthesias

- It begins at the lower extremities

- There are decreased or absent reflexes

- However in some variants, reflexes are retained or even increased.

- Patients may also present with

- Respiratory distress due to diaphragm weakness

- Haemodynamic compromise due to dysautonomia.

Risk Factors for developing GBS

Infectious Causes

- Viral: CMV, SARS-CoV-2, Zika, EBV, Dengue, Measles, Influenza, Enterovirus

- Bacterial: Campylobacter jejuni, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae

Vaccinations

- Influenza, Measles-Mumps-Rubella, COVID-19

Medications

- Ipilimumab, Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab,, Atezolizumab,, Durvalumab

Medical Conditions

- Surgery, Pregnancy, Myocardial Infarction

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnostic criteria shown below, should be used as a screening tool and may not be as helpful in the emergency department:

- The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and

- The Brighton Criteria (appears to have a higher sensitivity)

Brighton Criteria

- Bilateral and flaccid weakness of the limbs

- Hyporeflexia/areflexia in weak limbs

- Monophasic course and time between onset-nadir within 12hours and 28 days

- CSF cell count < 50/mL

- CSF protein concentration >60mg/dL

- Nerve conduction studies consistent with a GBS variant

- No alternative diagnosis for weakness.

Investigations

The diagnosis of GBS is mostly clinical.

Labs: Potassium and Phosphate, to exclude hypokalaemia as a diagnosis.

CSF: Elevated protein and a cell count of < 50 cells/microgram of fluid (cytoalbuminologic dissociation) can suggest GBS. The earlier in the course of the disease that the LP is performed, the lower the rate of cytoalbuminologic dissociation. If performed between 0-1 days after symptom onset only 50% have cytoalbuminologic dissociation in the CSF. This number increases to 88% at 3 weeks post symptom onset. We should not rely on CSF to make the diagnosis.

Neuroimaging: Although does does not directly diagnose GBS, it may assist in diagnosing other causes of weakness or paraesthesia. MRI is the preferred imaging choice.

ED Management of GBS

The main area of management in the emergency department involves the stabilisation of the patient and any airway or respiratory intervention that becomes necessary.

The ascending paralysis affects the abdominal muscles, the diaphragm and the intercostals, which may affect ventilation, resulting in hypoxia and hypercarbia. Generally, respiratory compromise or fatigue will require intubation as NIV is considered a temporary fix and increases the risk of aspiration.

Findings suggestive of the need for intubation:

- Difficulty clearing secretions

- Unable to cough effectively

- Dyspnoea or difficulty breathing

- FVC < 20mL/kg or a drop >30% in repeat readings or negative inspiratory force < 30cm H20

- Hypoxia/Hypercarbia

- Single breath count < 20

- Vital sign abnormality ie., tachypnoea or tachycardia.

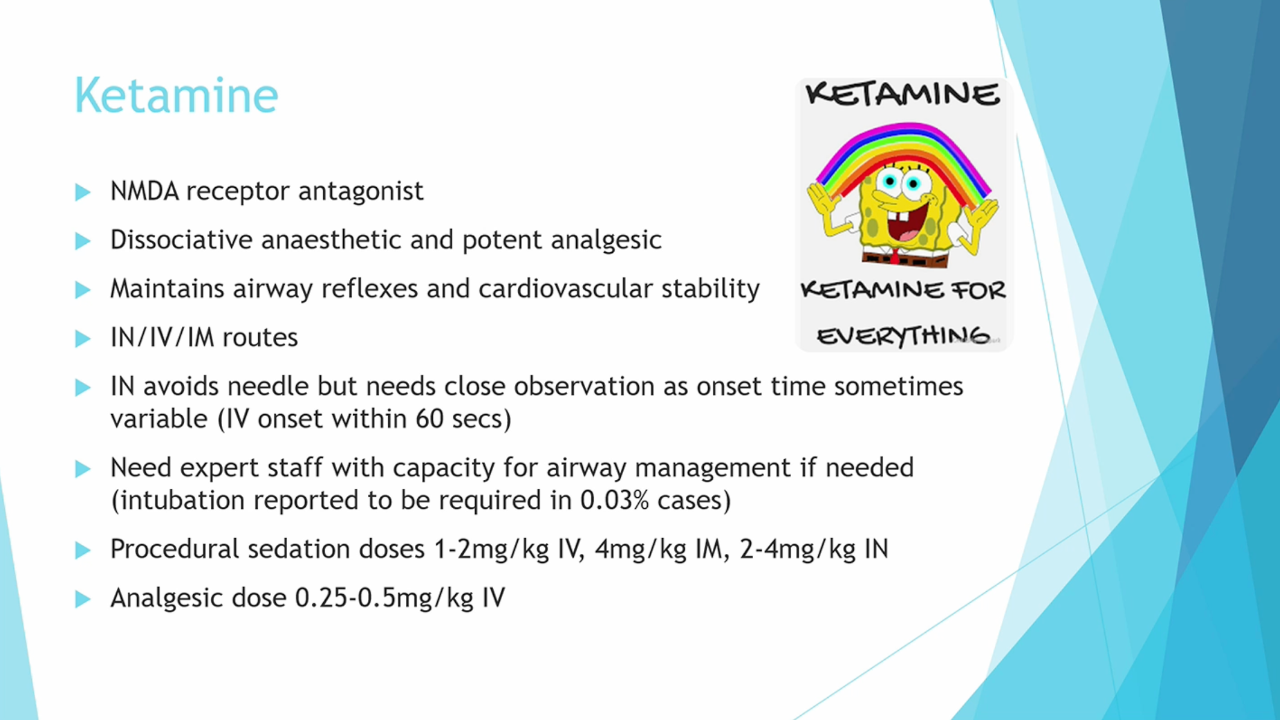

When performing rapid sequence intubation (RSI), it is best to avoid succinylcholine as it may result in hyperkalaemia. Rocuronium is the drug of choice. Normal dosing may result in more prolonged paralysis, however this must be balanced against gaining a more rapid onset of paralysis. If needed sugammadex can be used to reverse the paralysis.

Dysautonomia can be transient or prolonged and can result in

- Arrhythmias such as sinus tachycardia (most common), ventricular arrhythmias, bradycardias and even asystole.

- Abnormal blood pressures. Severe hypertension can occur and has been associated with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome(PRES). Patients may present with visual disturbances/loss, altered mental state and seizures.

Management of dysautonomia may include:

- Labetolol or esmolol for hypertension

- Adrenaline for bradycardia and hypotension.

- Pacing

The definitive treatment of GBS is by use of intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange. This will be done in consultation with neurology.

Conclusion

GBS is a low prevalence, high stakes disease. We must consider the diagnosis in patients presenting with neurological deficits. Although the classic presentation of ascending symmetrical flaccid paralysis. preceded or accompanied by paraesthesia is the most common presentation, atypical presentations including no weakness, or upper extremity weakness, or cranial nerve abnormalities may mimic stroke or other conditions.

Our management is related mostly to supporting any respiratory compromise that may occur and dealing with the less common dysautonomia that may occur.

References

- Madden J et al. High risk and low prevalence diseases:Guillain-Barre syndrome. AM J Emerg Med 75(2024) 90-97 PMID: 37925758

- VandenBerg B, et al. Guillain- Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014 Aug;10(8):469–82. PMID: 25023340.

- Arcila-Londono X, Lewis RA. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2012 Jul;32 (3):179–86. PMID: 23117942.

- Dimachkie MM, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome and variants. Neurol Clin. 2013 May;31(2):491–510. PMID: 23642721

- Kalita J et al. Prospective comparison of acute motor axonal neu- ropathy and acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy in 140 children with Guillain-Barré syndrome in India. Muscle Nerve. 2018 May;57(5): 761–5. PMID: 29053890.

- Notturno F,et al. Acute sensory ataxic neuropathy with anti- bodies to GD1b and GQ1b gangliosides and prompt recovery. Muscle Nerve. 2008 Feb;37(2):265–8. PMID: 17823951.

- Fokke C, et al. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain. 2014 Jan; 137(Pt 1):33–43. PMID: 24163275.

- Huggins RM, et al. Cardiac arrest from succinylcholine-induced hyperkalemia. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2003 Apr 1;60 (7):694–7. PMID: 12701553.

Join Our Free email updates

Get breaking news articles right in your inbox. Never miss a new article.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.